The Crystal Palace, London - The Great Exhibition, 1851.

The History of Lincoln Waites

Sibthorp for Ever

Tune: "Scots wha' ha' wi' Wallace bled."

1826 - 1837

The Broadsheet is undated, however, there are some clues! Scots Wa' Ha' was written by Burns no later than around 1790. Canwick Hall (at Canwick near Lincoln) is mentioned is the song because this was the seat of the Sibthorp family from the 17th Century, yet this song mentions our King - so it must have been written before the reign of Queen Victoria, which began in 1837.

The Sibthorp Family

The Sibthorp family were very influential. Family members include the botanist John Sibthorp (who, in 1790, was corresponding with Sir Joseph Banks - the botanist who travelled with Cook to Australia). Various members of the family were members of the priesthood; serving in the Army or Navy; or Members of Parliament.

Humphrey Sibthorp II, was Colonel of the South Lincolnshire militia during a period when the Irish rebellion followed by fears of a French invasion kept the militia fully occupied. At one point the Sibthorp family represented the three lines of defence against Napoleon: Henry was in the fleet cruising off Boulogne and Charles was in a cavalry regiment on the Kent coast, while their father, Colonel Humphrey, was with his Militia in reserve near Colchester. (Archivist's Report 18, 1st April 1966 - 31st March 1967, Lincolnshire Archive Committee)

Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorp (1783-1855)

I believe that the Broadside "Sibthorp for Ever" was probably written about Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorp.

Charles, like most of the family went to Oxford, his college being Brasenose, but failed to graduate, joining the army instead, while still in his teens, serving in the Royal Scots Greys first, [this explains the Scottish tune and the suggestion of a Scottish accent, as the words of this ballad hark back to Charles' early military service] and later with the Dragoon Guards during the Peninsular War. He remained in the Army after the Napoleonic Wars, until 1822, when he succeeded to the family estates. He married Maria Tottenham in 1812 and they had four children.

In 1826 Charles had been elected as the Tory Member of Parliament for Lincoln, following his father, his brother and his great-uncle, and like them he became Colonel of the South Lincolnshire Militia. Charles was continuously MP for Lincoln from 1826 until 1855, except for 1832-1835. The Gentleman's Magazine for January 1856 says: "Colonel Sibthorp ever retained a strong affection for his original profession - shown in the ardour and profuse liberality with which he endeavoured to advance to perfection the militia regiment of his county after his appointment as colonel." He was a Deputy-Lieutenant of the County and a Magistrate. He possessed great personal as well as family influence and was popular [with some people] due to his habit of "calling a spade a spade."

Soon after election to Parliament, Charles entered the debate on the Reform Bill. He opposed it in all its stages, though the clause regarding better provision for the residence of clergy and enabling their widows to retain possession for two months after the death of their husbands is said to have originated with him.

Charles represented Lincoln in Parliament until his death, except for a short period in 1833-1834. Few MPs took their jobs as seriously as him. He rarely missed a sitting of Parliament and was always ready to speak in defence of the "old order" of rural life - which was rapidly disappearing as machinery became popular and industrialism advanced. Even his bitterest opponents paid tribute to his honesty of purpose. Completely sincere, no prospect of place, honour or pension could induce the Colonel to vote contrary to his conscience.

During the debates on the emancipation of the slaves, a distinct group of abolitionists emerged, led by William Wilberforce. They became known as the Saints. Charles was in this group. Feelings were strong on both sides, and many MPs wanted to take part in the debates. Those who arrived late did not get a place, so sat on benches below the gangway, or stood up. Some MPs were unable to gain admittance at all, because the House was full. At this time, Charles began lodging at a nearby Tavern overnight so that he could arrive at the House of Commons before 8.00 am, in order to save places for all the 'Saints'.

His opponents hated the clear and utterly single-minded manner (or blunt manner - depending on your viewpoint) in which he expressed his opinions. During his thirty years in Parliament, he became renowned, along with Sir Robert Inglis, as one of its most reactionary members. He strongly opposed Jewish Emancipation, Catholic Emancipation, the Repeal of the Corn Laws, the Reform Act of 1832, and the 1851 Great Exhibition. The style he used, when arguing his political views, made him the target of outrage in The Economist and witticisms in Punch.

In December 1832, Charles' popularity among the people [ladies?] of Lincoln led them to present him with an expensive diamond ring as a Christmas gift. It is inscribed; "The ornament and reward of integrity presented to Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorp by the grateful people of Lincoln, Christmas 1832." This ring and other Sibthorp items can be seen in the Usher Gallery, Lincoln.

In December 1839 the Colonel, proposed a successful motion to Parliament to reduce Prince Albert's annuity - from £50,000 to £30,000 - on the grounds that the Queen was marrying a foreigner (Queen Victoria shunned him for the rest of his life).

Charles was fiercely Protestant and his brother Richard's conversion to Catholicism in 1841 only fuelled the Colonel's religious sectarianism.

Between 1830 and 1850 were years of acute agricultural depression. The corn laws of 1815, which had aimed at preserving the farmers' monopoly of wheat, had brought utter misery to the farm labourers. Many tenant farmers as well as those who owned small acreages were facing financial ruin. Many Tories supported a repeal of the Corn Laws, but Colonel Sibthorp made a furious attack on Peel's turncoat policy. The repeal came in 1846 at a time when railway mania was at its height.

One of the petitions to Parliament in 1846 was presented by Lord Grimston MP, on behalf of the people of North Mymms, Hertfordshire. He objected to the plans for a new railway to run through their parish. This petition immediately drew Charles' support, especially when he saw the engineer's plans. But the petition failed and the engineer, Cubitt, built his railway from London to York. It cut through the orchard at Skimpans (Charles' childhood home at North Mymms) and Cubitt erected an eyesore of a bridge across the pleasant grassy track that led to Foxes Pit and on to the turnpike that Charles had travelled to Lincoln on, when visiting his grandparents as a child. Charles hated the railways for desecrating his childhood home and often spoke out, in opposition to them.

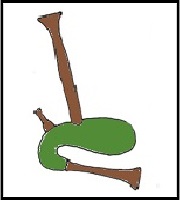

Contemporary cartoon of Colonel Sibthorpe, depicting him attempting to limit the growth of the Railways. Picture reproduced with permission of Richard Hawes of The Lancashire Gallery.

Charles led a group of MPs and Gentry who opposed Prince Albert's Great Exhibition project of 1851. In fact, he called down curses from Heaven to destroy the glass roof of Paxton's "great greenhouse". Charles' hostility toward free trade and foreign influence found a target in this exhibition promoted by a GERMAN Prince. Before the House of Commons on February 4, 1851, the Colonel called on God to send "a heavy hailstorm" to destroy "that fraud upon the public called . . . the 'Crystal Palace' - that accursed building, erected to encourage the foreigner at the expense of the already grievously-distressed English artisan." Having already angered Queen Victoria he went on to declare that the Great Exhibition would bring the plague to England! He continued to denounce the Great Exhibition on the grounds that it encouraged foreign competition and foreign visitors [spies] into England. Sibthorp felt deeply suspicious of all foreigners. He believed that foreign agents would use the Great Exhibition in order to enter Britain to spy into our dockyards, our weaponry and our fortifications. The nation, he predicted, would pay dearly for her misplaced hospitality.

On 27 August 1851 Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the royal children were travelling by train to Scotland. The route to the north passed through Boston, Spalding and Lincoln and then on to Doncaster. When the Royal train stopped at Lincoln, Lord John Russell stepped off the train to introduce the Mayor to the Queen, but Victoria did not alight. (Lincolnshire Chronicle, 29 August 1851). The City had been decorated as if a full-blown Royal Visit was taking place. There were flags and bunting everywhere, perhaps the Mayor had hoped that the Queen would step off the train, at least for a brief visit, but no, he was to be disappointed. Rumours soon spread that the Queen refused to tour Lincoln because of her dislike of Colonel Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorpe. The Great Exhibition had opened in May of 1851. Queen Victoria remembered Sibthorp's opposition to it, and his part in having Prince Albert's annuity reduced only some three months before.

In one of his speeches in the House of Commons, Charles said that he considered it an honour to belong to the South Lincolnshire Militia, as there was not a body of men, anywhere in the world, finer than the corps that he had commanded. It becomes apparent in the rest of this entry, that he had spent a considerable amount of his own money in equipping and training the Militia to a high standard. He begged to assure the Government and the Crown that he would go to any lengths to keep the Royal South Lincolnshire Militia in the most efficient state - and that he would continue to spend any energy necessary, as well as subsidising them financially, to make them in every way worthy of the country, and able for any service, whether foreign or otherwise, that they might requested to perform. (Royal Inquiry into the Court Marshall of Earl Lucan. Hansard - col. 1310. House of Commons 29 March 1855).

Towards the end of his days, even at nearly seventy, and despite being unwell, Charles' attendance in the House was as regular and his outbursts were as frequent as ever. He was one of a minority of fifty-three who censured the Free Trade Bill introduced by Earl Grey in 1852. He was a man of strong convictions, a Tory champion of all that was gracious and peaceful in rural England. Colonel Charles de Laet Sibthorp was a product of his time, and his experiences. He was a disciplined soldier and leader, who held the security of his Country and the protection of his Religion as his main priorities.

If I am right, and this song is about Colonel Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorp, my original rough date range of 1790 - 1837 (1790: Scots Wa' Ha' written, 1837: England now has a Queen, rather than a King) can be further shortened. As Colonel Sibthorp became an MP in 1826, it is likely that the song was written between 1826 and 1837. [My thanks to Chris Gutteridge of the International Guild of Town Pipers for his help with these dates.

Update from The Society of Lincolnshire History and Archaelogy, 04 May 2010

Subject: Sibthorp for Ever

"Dear Al,

I can offer some help in dating the song 'Sibthorp for Ever' on your Lincoln Waites website. It appears in a Poll Book for the Parliamentary Election for Lincoln of 1826 (the book can be seen in Lincoln Central Library). The song is also due to appear in a book about Col. Charles Sibthorp of which I am a co-author.

Best wishes."

Mark Acton

As Lincoln retained Waits until 1857, it is possible that they may have seen, heard or even, perhaps, sung this song. They may have actually met the Colonel himself.

If you would like to hear my own arrangement of the tune - please click the following link:

- Let your heartiest shouts resound,

- Freemen! While ye rally round

- Sibthorp, who will stand his ground,

- True to Liberty!

- Freemen stand, or Freemen fa',

- Popedom quakes at ev'ry blow,

- Slav'ry trembles as ye go,

- Sibthorp wi' to meet the foe!

- Far above a bribe or fee,

- Friend of Freedom, and the Free;

- He your wrongs will righted see,

- 'Mid contending rage:

- And when social joys recal,

- From cares of state to Canwick Hall,

- Firm your friend, ye one and all,

- Sibthorp sure will always find!

- Come then, Freemen, let us sing,

- 'God save, Sibthorp, Church, & King!'

- Bacchus sure will mirthfu' fling,

- Round us wreathes of jollity:

- In a bumper three times three,

- 'To the Mem'ry of the Free!'

- While the Gods in cheerful glee,

- Echo back to earth, 'Amen!'